In a brain like this: the sequel

"2 Slow 2 Curious: Autistic Boogaloo"

The wave of correspondence that followed my previous post, in which I discussed my diagnosis of autism, has been a pretty clear sign that you want more on this topic. You’ve also really boosted my confidence in discussing this issue (thank you), and asked plenty of questions, mostly about specific symptoms and how they manifest themselves. So, here we go! Autism post number two!

In preparation, I re-read my eighteen-page assessment report (now buried again in the deepest darkest cupboard), and more pleasantly, a wonderful book called A Different Sort of Normal by Abigail Balfe. While not a thin volume, it was written with such a light touch (and with so many cartoons) that it was an almost effortless pleasure to breeze through over a single weekend, with time left over to write this post and typeset a 300-page novel.

The book is billed as “a real-life true story about being unique”, and the author certainly does come across as unique – gloriously so, in fact. Helpfully, she’s also very different from me (there’s a whole thing with toilets that had my eyes on stalks), and her female perspective separates us a touch further. As such, my thinking was that any symptoms discussed in Ms Balfe’s book which I’ve also experienced must be somewhat universal, and therefore, a good framework for this post.

I haven’t sought her permission, so if you ever read this, Ms Balfe, I hope you don’t mind, and thank you for your contribution! (I’ll call you A.B. going forward; the whole ‘Ms’ thing feels a bit weird, but so would just using your first or last name.) I find it essential to check my own thoughts against other reliable sources (in this case, the report and the book), which is normal when writing, but might be an autistic symptom when carried over into real life. It’s a need to regularly check in with reality, to make sure I’m not missing something, and that I’ve not completely disappeared into my own world. (Unless I want to, of course, but there’s a time and a place.)

That symptom is not in the book, however. The first few that are could come under the heading:

Communication problems

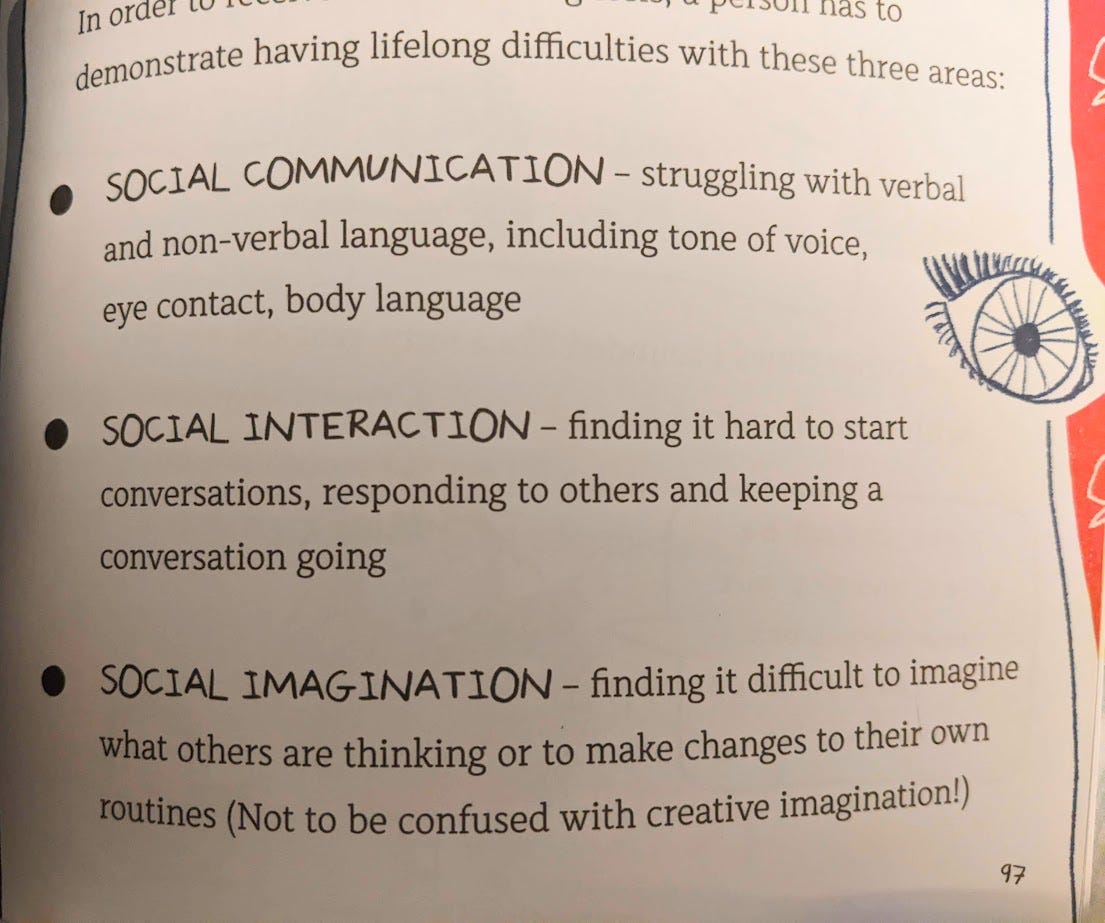

The above is a page from A Different Sort of Normal – I won’t steal any others, but this is a really key area, and expressed perfectly. This gets three big ticks for me. As the sentence above the bullet points (which I seem to have cut off) states, difficulties with these areas are an essential part of the autistic experience.

In my report, these were discussed under headings like “difficulties in non-verbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction” and “difficulties in social-emotional reciprocity”. I have made several efforts to study these topics, but unlike French or German (which fit nicely into a set of dictionaries), there seem to be enough variations in body language and tone to prevent me from ever being completely fluent.

Besides, translating what other people are doing is just part of the issue; the bigger problem is mastering outgoing communications. A.B. shared a painful and familiar anecdote involving an incident at a swimming pool party, during which:

“No one could sense my discomfort. I did not react verbally, and my facial expression probably remained the same throughout the experience too.”

She recalls numerous other instances of her “face not making the right shape”, and this was mirrored in my report as “facial expressions not matching content of speech”. I often trip over this, on one occasion accidentally smiling through a meeting in which someone was being made redundant (partly nerves, perhaps), and on another, remaining chipper and bright during ten days in hospital, nil-by-mouth, with a mystery stomach complaint. I couldn't keep any food or drink down for more than five minutes, but a week went by without anything being done about it. Eventually, a nurse just said outright: “If you want to get out of here, you need to act more ill! The doctors aren’t taking you seriously.” I did my best, and everything soon worked out – though on reflection, the painkillers must have contributed to my good spirits too.

Those are extreme examples, but I would say not a week goes by without me consciously reaching around, sometimes in a panic, for the right facial expression to suit a particular social encounter. As A.B. says, “people expect your face to match theirs”, and I suppose it’s not an unreasonable expectation. We just can’t do it!

Communication problems can lead to a lack of “congruence” (my own term) with the rest of the world, a phenomenon which left me utterly baffled until my diagnosis last year. One example of this is an anecdote I’ve often told, about the end of my time as a student teacher, in 2008, just before I came up with the idea for Valley Press. My supervisor looked through the exercise books of the children I’d been teaching for the past five weeks and said: “It’s remarkable… I’ve never seen anything like it. They actually know less now than before you started teaching them.” He then showed me enough examples that it stopped being funny.

“But why?” I asked, at a loss. I’d been doing everything the textbook said, the pupils were bright, attentive and well-behaved, and I was even wearing a suit – they just weren’t learning anything. It was as if there was some magic to teaching I couldn’t figure out. I spent the next decade telling and retelling this story, hoping someone would enlighten me – but sitting here now, it seems obvious the “magic” was in the social communication issues described above. I guess tone of voice, eye contact and body language are important parts of teaching, after all…

Similarly, I’ve never been able to get a graduate job, despite trying solidly for eight months in 2010 and a couple of three-month periods in later years. You’d better believe I worked hard at the process, with a brilliant CV (including early VP successes), a first-class degree in English Literature, and the highest level of preparation for the interviews one could reasonably expect. Yet, no joy. (Admittedly, when I finally gave up and started full-time publishing at the start of 2011, one of the authors said straight-faced: “Thank the Lord, I was praying you wouldn’t get a job.” So, other factors may have been involved.)

My mum hates it when I write publicly about these “failures” (sorry mum, last time), but everything worked out for the best, and I like to think if I’d stuck with the job hunt forever, I would have eventually got a position somewhere forgiving. Nonetheless, it became another area of confusion I would revisit over the years, trying to understand; to such an extent that one of my three-month job hunts, in 2019, was primarily started just to see if anything had changed. To still make no progress then was a little unsettling.

A.B.’s smartly-worded take on this is as follows:

“As an autistic person, I often feel like everyone knows something I don’t. Like they’re all in on a joke that I just can’t understand or see the point of.”

That feeling, which I frequently share, must involve something deeper than body language and tone of voice – and it certainly extends beyond teaching practice and job interviews. I still don’t fully understand the reasons behind it, but I’ll let you know if and when I do.

Onto the next symptom, which is actually just this one in a different context; but it feels like another subheading is due, don’t you agree?

Emotional opacity

As A.B. reports, contrary to the stereotype, autistic people are often extremely empathetic. I feel plenty – the word “feel” appeared in the last three paragraphs! – and I connect very deeply to emotions in literature, art, film and (especially) music. Unfortunately, due to the communication problems described above, unless you are using one of these art forms (or performing like you’re in a stadium not wanting the back row to miss anything) I most likely have no idea how you’re feeling. I also find it virtually impossible to express how I’m feeling, via anything other than music or poetry. (That’ll be the “social-emotional reciprocity”, then.)

As you can imagine, this is not ideal for relationships – but the answer, for both sides, is to communicate bluntly and clearly. “I am sad about this,” etc. Being six years old also seems to help, as I never struggle to understand how my son and his friends are feeling; though of course, they aren’t especially subtle under any circumstances. (In my own childhood, I could read my friends’ emotions confidently up to the age of 11.)

What is it about music and poetry that helps? I’m still working on this theory, but it’s something akin to capturing wild emotions on a page like pressed flowers, or like butterflies in a jar (except not so cruel – as, ironically, emotions don’t have feelings). Once they’re there, in that stable, repeatable and examinable state, they can be unpacked and understood at my leisure. (Speed is also not one of my strengths.) Of course, this could also be a side-effect of…

Sensory reactivity

“I experience everything very intensely,” says A.B. – or less poetically, as our other source puts it, she experiences “hyper-reactivity to sensory input.”

I would put prolonged eye contact, briefly discussed earlier, under this heading. I find it excruciating, but not exactly painful – the feeling is more akin to having the bottom of my feet tickled, an “intense” feeling that I can’t keep up for long. As such, I believe for me, avoiding eye contact is a sensory issue rather than a “social cues” one.

My other triggers include polystyrene and flavoured crisps; if you’re squeaking the former or scoffing the latter (any flavour will do) I will literally have to leave the room. I also have a thing about big, bright overhead lights – at home, I use mine so rarely that dust accumulates on the switches. Daylight or dim yellow lamps only, please. Oh, and I hate the texture of berries, and loud noises. That’s about it.

When I was at university, these sensory issues meant I couldn’t really go into nightclubs, or even a noisy bar. (No one suggested ear defenders back then; but in any case, you know how I’d have fared going on body language alone!) I would still go out for the first part of the night, only to harm my already fragile social “cred” with over-the-top enthusiasm about how great this place was. “Isn’t it wonderful! I can hear every word you’re saying. This beer was so expertly poured. Let’s stay here forever! Why move on at all? Guys, wait – come back!”

However, this symptom can cut both ways. Sensory reactivity can make many elements of life more enjoyable; I have a big thing with music (see above), and I share with A.B. a love of extremely soft items of clothing, especially jumpers. One of my eccentric behaviours when younger was wearing a jumper when it was absolutely not the correct occasion (e.g. on a very warm day; and the one time I did step inside a nightclub, I was wearing a jumper). In the first draft of this post, the next sentence read “I’ve mostly avoided that for the past year” – but then I fell into this exact trap on Saturday after a weather mix-up (it was 23°C!) Gosh, that jumper felt good, though.

Stimming

This is “a self-soothing behaviour marked by a repetitive action” (to quote both A.B. and the assessment). I saw this symptom manifest itself the other night at a restaurant, as I sat across from two adults, only one of which I knew well. As A.B. says:

“One-on-one conversations can be amazing and special and fun. With more than one person, they can be an overwhelming assault on the senses.”

Besides the usual eye-contact apocalypse, I found myself facing a profound need to fiddle with a little metal table number sign throughout the whole experience. After a few attempts to stop, I decided to let myself carry on to my heart’s content – as discreetly as possible – and ended up having a brilliant evening.

Another “stimming” behaviour is swinging in my chair, which apparently I did throughout my autism assessment. I first discovered this during a double Valley Press book launch on Zoom; two minutes into my introduction, I noticed the chat box had filled up with messages saying: “Stop swinging in your chair!!” The kind souls must have been worried I’d break it. (Naviety is another symptom, of course, but we talked about that last time.)

If an autistic person is prevented from stimming, trouble can arise, including what A.B. refers to (brilliantly) as “situational involuntary mutism”. This is where an autistic person loses the ability to speak, which has only happened to me three or four times, in every case whilst dining with a large(ish) group. If you can recall saying to me, in concern, “You haven’t said a word all night” – that was one of the times. If you also wondered why I disappeared to the bathroom for twenty minutes, I was resetting myself with some peace and quiet. (Maybe had a wee too.)

With the above in mind, the thought of attending the forthcoming Laurel Awards ceremony does somewhat chill the blood, but it’s such a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity I wouldn’t dream of turning it down. You’ve got to live, after all. For those few hours, I will do my best to make occasional eye contact, take part in small talk (but not too enthusiastically, which can be just as odd) and not reply to someone introducing themselves by saying “Okay!” (another awkward habit). Then again, it is a room full of poets, so perhaps they will be looking to me for social guidance…

Love of routines

I tend to be highly methodical, and apparently this is a symptom too. One of the big indicators I showed during the assessment was, upon being asked how I brush my teeth, going into excruciating detail far beyond what could possibly have been called for, incorporating everything I’d read (and a few things I’d debunked) about good dental hygiene. I must have been talking for quite a while. Someone asked me the other day about my routine before I leave the house: five minutes later they were asking me to stop talking. (But, this is really an example of the next symptom.)

I’ve written another post, to be sent out next week, discussing the thirty-step “production process” Valley Press books go through from file to shelf. I wonder how many other publishers have these, follow them to the letter, and get anxious when forced to go off-piste? I’d assumed everyone did that – but now, not so much.

Info-dumping

Info-dumping is a side-effect of what my report calls: “Highly fixated interests that are atypical in intensity or focus”. It’s a phenomenon in which autistic people will unexpectedly share information on a particular topic in a single great burst.

A.B. notes: “Enthusiasm and fascination are powerful and magnetic; no one should make you feel bad for loving what you love” – but also, this can cross over with social communication issues: “I can find it difficult to work out whether someone is enjoying it when I ramble about my favourite topics.”

I apologise to anyone I’ve done this to over the years. Pre-diagnosis, a friend wisely observed: “You’re either not into something at all, or you know enough to write a short book about it – nothing in between.” That comment was so spot on, and my areas of intense interest are as numerous as stars in the sky: to name one random example, I became fascinated by prolific songwriter Francis ‘Eg’ White and spent weeks listening to and privately ranking every song he’d been involved with (there are hundreds). If I met up with you during that time, I’d trick you into a conversation about Eg’s work with a comment like: “Hey, do you remember Adele’s ‘Chasing Pavements’?” and then – well, lord help you.

However, I’ve now found a healthy outlet for my info-dumping: this blog! Have you read any long, extensive essays, based on my intense research into a particular area of interest, lately? Yes, I’m afraid you’ve been info-dumped, and in fact it is still happening right now. Oh, you are in for some treats in the coming months!

One of my more well-known interests is snails, and this extends a little beyond the factual; if I see a snail on the street, I will pause for a minute to watch their progress, potentially move them to a more suitable area, and – if no one’s around – have a brief chat. (That’s not autism; I don’t know what’s going on there.) I also wrote a book of snail poems, which was one of the first VP publications, and is now available from The Emma Press. My first contact with Kate Fox, back in 2012, was to ask for a cover quote for the second edition – and she mentioned during our post-diagnosis chat (recounted last week), that she’d assumed all along the snail itself was a metaphor for autism. I’m still getting to grips with that thought.

I think that’s your lot for today – phew, got a bit carried away there! I still owe you a post about how I’ve adapted the day-to-day business of publishing to fit around some of these shortcomings; and in fact, there could be a fourth post about how autism helps with publishing, which would be a nice dose of positivity. (A clue: it involves spreadsheets.) I’ll be delighted, as ever, to receive your questions on what I’ve discussed above – though I’m still very much a novice, and you may prefer to consult a specialist organisation such as the National Autistic Society.

In any case, take care, keep smiling (if the current social situation calls for it), and I’ll see you soon.

Very interesting to read and humorous too. I can recognise some of the behaviours descibed , in people l have known.

I was a college lecturer ( part time) for six years . When l left it, for financial reasons, to get a full time job, it felt like a big relief!