Guest week: When Hongwei Met Simon

Queering place and identity, from China to the Isle of Man

Hello all! It’s time for a few more guest posts, the first being a discussion between Valley Press poets Hongwei Bao and Simon Maddrell. With history, place, folklore, culture, politics, and queer identity being key touchstones for both, I felt sure they would have plenty to discuss – and as you’ll see, I was right…

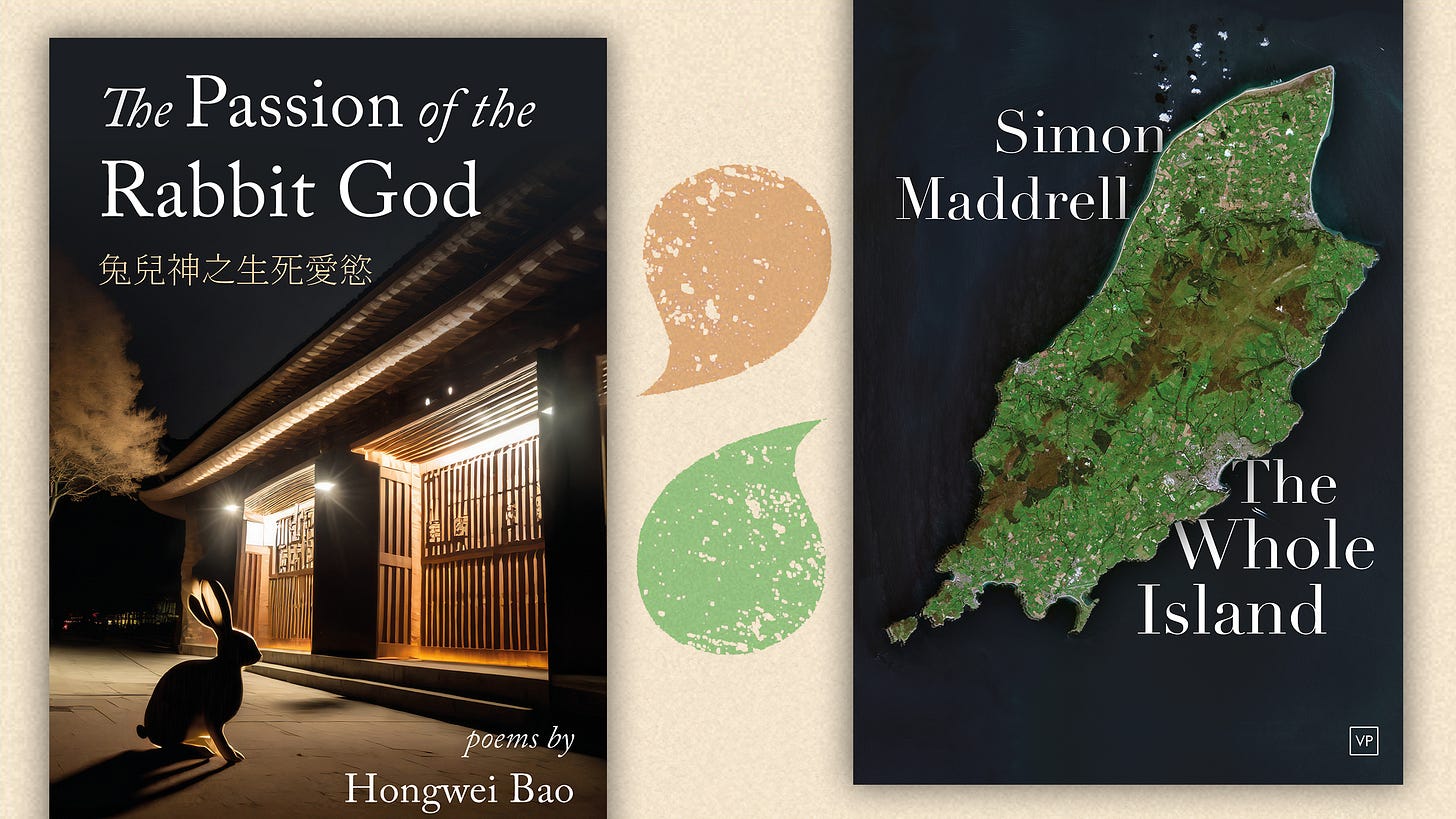

Hongwei: Simon, your wonderful poetry pamphlet, The Whole Island (Valley Press, 2023), dives into the history, geography and culture of the Isle of Man, as well as your experience of being gay and Manx. The island imagery is everywhere in the book, and even on the cover (which shows a satellite image of the island) and in the title. Could you talk about how you settled on the book title and cover image, and what you hoped to convey to your readers when they came across the book for the first time?

Simon: The choice of cover image is all credit to Jamie McGarry, our publisher. Because of the book title, we agreed that an image of the island was better than the famous triskelion “Three Legs of Man” and he did the rest. The title, The Whole Island, came from the first poem written for the book, which I had intended as the first poem but my editorial consultant, Kate Simpson, smartly suggested should be the central poem instead. (NB: Kate was an ‘Editor at Large’ for Valley Press from 2020-2022, who also supervised the anthology Out of Time and Emma Must’s The Ballad of Yellow Wednesday.)

Kate best captured what the book is about in the original press release:

The Whole Island explores the poet's relationship with the Isle of Man, in poems which touch on family and folklore, history and politics, nature and wildlife, as well as their tangled connections. Through lines that charm and blaze, Simon Maddrell considers what it means to be endemic: the island navigated as a body, the body as an island. Here, the poet calls upon his cherished Isle as an allegory for the nature of his own queerness, the queerness of nature, and the threat of extinction more broadly: linguistic, cultural, physical, environmental.

The titular poem was inspired by the Cuban poet Virgilio Piñera’s epic La Isla en Peso which was originally published as a chapbook in 1943. It is translated as The Whole Island even though, equally appropriately, the literal translation is “the weight of the island.” La Isla en Peso captures the ambivalence, contradictions, and dissonance of the socio-political landscape in Cuba from an insider/outsider perspective, which resonated with my own feelings and my writing about the Isle of Man in my chapbook, Throatbone, which also included work inspired by Manx poets.

So, I wrote my own shorter version of Piñera’s poem. The poem captures ambivalence too, but perhaps less 'love & hate' and more 'joy & sadness' as the extreme emotions. At the last minute, the titular poem’s title was changed from 'The Whole Island' to the Manx Gaelic, 'Yn Clane Ellan'. It fascinates me how much courage it took to embrace the Manx Gaelic more fully, to overcome that internal dialogue telling me that ‘the English will feel alienated by the use of a foreign language.’

(N.B. The 2010 translation of La Isla en Peso by Mark Weiss, The Whole Island, is available for free download from Shearsman Books.)

Hongwei, your debut collection, The Passion of the Rabbit God (Valley Press, 2024) has many resonances with my book. But for you, what came first – the book title or the titular poem? Whilst choosing the Rabbit God, the patron god of LGBTQI+ people, to include in the title – are there any 'less obvious' reasons, and why specifically have you centred on ‘The Passion’? And what about your cover artwork?

Hongwei: Two poems, ‘Confession of the Rabbit God’ and ‘The Passion of the Rabbit God’ came before the book title. I have always been fascinated by the ancient Chinese myth of the Rabbit God. My original plan was to write a sequence of poems narrating the Rabbit God story from the Rabbit God’s perspective. But in the process of putting together the collection, I leaned more towards writing about my own experience as a queer Chinese migrant. This was partly because I needed a self-reflexive and self-healing space in the context of pandemic lockdowns and in the discovery of my own ageing. I quickly realised that the Rabbit God story can serve as a backdrop for my queer Chinese migration story. Both are about queer Asian identity and experience, and both highlight queer Asian perseverance under difficult historical and social circumstances.

By using the term ‘passion’, the book title invites association with a long history of cultural texts such as St Matthew Passion, The Passion of the Christ, The Passion of Joan of Arc, The Passion of New Eve and The Passion of Michel Foucault. In many ways, the Rabbit God story is a religious and/or a queer story: about a person’s desire, life, death, enlightenment and deification. The prologue poem titled ‘Passion’ explores the polysemy and ambiguity of the term ‘passion’, captured nicely by the Chinese phrase 生死愛欲 (life, death, love and desire) in the book title. In the book, although most poems are about queer love and desire, a few do touch on themes such as life and death (e.g. ‘Curve’, ‘Haunted Village’, ‘Liverpool 1946’ and ‘Lunar New Year’).

The wonderful book cover was also designed by Jamie McGarry. I liked the draft design (showing the silhouette of a rabbit sitting in front of traditional Chinese architecture in a night setting) as soon as I saw it. The image shows a strong contrast of small and big, light and shadow, and perhaps also love and hate, life and death, good and evil. It captures a dramatic moment of waiting and longing, defiance and resistance. The rabbit theme also appears in the poem titled ‘Chang’e’, the story of the Chinese moon-goddess, so using the rabbit image is appropriate. The book cover is dynamic, atmospheric and even slightly haunting. It is wonderful! (I shall add that I have received several plush rabbit toys from friends following the book’s publication, which is very nice of them. I have no intention to keep a pet rabbit yet.)

I like Kate’s The Whole Island blurb and think it sums up the book well. Could you also introduce the organising principle, or structure, of the book? How do the poems fit together?

Simon: The organising principle was to have ‘Yn Slane Ellan (The Whole Island)’ as the central poem, as it pretty much touches on all aspects that the book explores (which is why I originally thought to have it at the beginning). The rest of the book then explores certain aspects of that poem more deeply, whether it be folklore, language, nature, place etc. The book is more my emotional exploration that the reader is invited to join. In the case of The Whole Island, that is not a chronological journey, though I guess it is a metaphorical one; as the book preface is the poem ‘going home’ followed by the first poem, ‘Foddeeaght’ which loosely translates to ‘homesickness, nostalgia and longing’. The book ends with a poem, 'And when I look back' after the great Manx poet T. E. Brown (1837-1897) riffing off his Betsey Lee lines:

And when you look back it's all like a puff,

Happy and over and short enough.

I'd say the first half explores looking back on family and then wider explorations of our ships and Vikings. The second half again uses family as a kick-off to explore nature & language, then survival & extinction. I imagine different readers will experience this non-linear journey very differently.

I loved your prologue poem 'Passion' – especially those last six lines:

So sweet,

so delicious,

and yet so intoxicating

that I forget

the bitterness

that comes with it.

It seems to sum up the book in many ways, but I do wonder, and forgive my cheekiness, are these lines talking more to sex than queerness, or vice versa, or both equally?

Hongwei: Thanks for your generous reading of the first poem, which is also the prologue of the book. I am fascinated by, and in fact obsessed with, the capaciousness and ambiguity of the word ‘passion’. The term ‘passion’ certainly refers to love, sex and desire, as the bulk of the book tells a queer love story (with some implicit or explicit erotic scenes that await the readers’ discovery).

But passion can also be social and political. Here I am reminded of Sara Ahmed’s term of ‘the politics of emotion’, which describes the role that emotions play in both mainstream and alternative politics. Intense emotions can be channelled to endorse mainstream ideologies such as nationalism and patriotism; they can also function as a disruptive force for resistance, to create social change. For example, the last section of the book addresses some social and political issues, including heteropatriarchy in traditional Chinese society, ‘white paper’ revolution, Brexit and pandemic racism, as well as the UK government’s hostility towards migrants and refugees. Passion here becomes a call for social justice and a catalyst for social change.

Queerness for me is, therefore, not just being part of a sexual minority. It is also a process of becoming: becoming minoritarian, becoming different, becoming critical. It is a way of doing things, a catalyst for social change. The Passion of the Rabbit God primarily shows the narrator’s ambivalence towards, and uneasy relationship with, their childhood, family, national identity (both Chinese and English), sense of belonging, history, place and memory. It is their refusal to attach themselves to a fixed identity, a dogma, a straightforward answer and an easy solution, that best illustrates the spirit of queerness. I appreciate what Ali Lewis, author of Absence, says about the book:

‘Hongwei Bao's poems […] see the minute gradations and degradations of our shared and particular lives.’

The ‘queerness’ of your poems is well summarised in Kate’s blurb, ‘the island is imagined as a body, the body as island’. This is such a brilliant idea! Could you say a few words about this idea and how it is manifested in the book?

Simon: Queer writer, director and performer Neil Bartlett says that gender and sexual identity always comes back to bodies, especially our relationship with our own bodies. I guess it was inevitable that with such a distinct and small island as the Isle of Man, that poetry would utilise the island as a metaphor for the body, and being queer, one would see oneself, at times at least, as an island.

It’s the funny thing with blurbs, they describe ‘how the book turned out’ rather than that necessarily being what the aim was in the beginning. I have lived so long in different parts of England, but I have never perceived where I live as being an island. For me it is a whole range of separate entities joined together rather than feeling like an island in itself, so the Isle of Man engenders in me that feeling of an island, which probably engenders itself in my writing about it. Incidentally, the writer Dennis Potter described the Forest of Dean as a heart-shaped island surrounded by the rivers Wye and Severn and the A40. Having lived on the northern outskirts in Ross on Wye, I also could sense that island feeling and it had so many similarities to the Isle of Man because of it.

Your collection is structured in sections; can you tell me more about that choice and the choice of the sections and sequencing?

Hongwei: It took me quite some time to figure out how to structure the book and sequence the poems, but as soon as I anchored the central imagery of the Rabbit God and the key themes of queer love and Asian identity, the book structure became clearer to me: in four sections and roughly following a temporal trajectory and spatial movement – from the historical to the contemporary, from childhood to adulthood, and from China to the UK and then reflecting on the transit states of migration. The book therefore starts with retelling ancient Chinese stories (Section 1), followed by reflections on identity, childhood and sense of belonging (Section 2), then the evolution of a queer relationship (Section 3), ending with the contemporary situation and the articulation of a queer Asian diasporic politics (Section 4). But the actual execution is messier than its design, as the individual poems were written under various circumstances over three years, spanning a large part of the pandemic period. Inevitably, each poem entails a different style and emotion. I see the book as celebrating styles, emotions and modes of being rather than all of them being forced into a singular and coherent narrative.

Your opening poem ‘Foddeeaght’ dramatises ‘your’ and ‘his’ divergent feelings towards home, towards the Isle of Man (‘it’s a folly, to think I want to be / where he is’). This contradictory feeling seems to underpin much of your discussion in the book. Could you elaborate on what you hope to convey or achieve through the poem?

Simon: My prologue poem ‘going home’ sets up the book to be this exploration of a returning ‘exile’. The first poem ‘Foddeeaght’ is exploring the question of whether I miss ‘home’, and what ways across that spectrum of meaning of the words Hiraeth (Welsh) and Foddeeaght (Manx Gaelic). It was inspired by a question from a Welsh exile at the launch of Throatbone, but actually prompted by reading Golnoosh Nour’s ‘Hiraeth’ in their collection Rocksong. What is central to the poem is Hiraeth, because it doesn't have a direct English translation and covers a range of emotions including after the loss or death of someone/thing: e.g. homesickness tinged with grief and sadness, longing, yearning, nostalgia, wistfulness or earnest desire. The poem attempts to explore some of those emotions in concrete ways, rather than ‘say’ something concrete, which I guess is exemplified by the fact that it appears to contradict itself, maybe.

In your first section, would you say that the Rabbit God is your mask for the ‘lyrical I’, or simply a tribute/homage to the god's existence during the Qing Dynasty?

Hongwei: It can be both. The Rabbit God story is part of queer East Asian heritage. The story was often told in a third-person perspective in classical Chinese literature, the best known of which is Qing Dynasty scholar Yuan Mei’s Zibuwu (What the Master Would Not Discuss, 1788). There were some Rabbit God temples in different parts of Asia, but very few of them remain. Many people in East Asia do not know the story due to a long history of queer erasure from official narratives. Some still think queerness is a Western import. Politicians in Asia sometimes make use of nationalism and cultural essentialism to suppress queer people, suggesting that queerness is Western and un-Asian and should therefore be eradicated. By rewriting the Rabbit God story, I hope to draw attention to the fact that there is a long queer heritage in Asia and queerness is native to Asian cultures. I also hope to give queer Asians a voice by making the Rabbit God speak. There are politics and ethics involved in making historical figures speak in persona poems, but I hope I have done the Rabbit God story sufficient justice through my own historical and archival research.

The Passion of the Rabbit God is written from the first-person point of view; that is, there is a seemingly consistent ‘lyrical I’ voice throughout the book. But the ‘I’ may refer to different people in different poems. In Section 1 alone, it refers to the Rabbit God, a queer poet named Qu Yuan, the female protagonist Zhu Yingtai in the Butterfly Lover story, and the Chinese moon goddess Chang’e. In other sections, the lyrical ‘I’ is used to narrate the story of a young, queer Chinese person, growing up in China and migrating to the UK, coming to terms with his sexuality as well as his racial and ethnic identity. The speaking subject of Section 2, ‘Queer Intimacies’, is a young queer person around university age, and that person is definitely much younger than me. I find a young person’s voice particularly effective in narrating a queer love and migration story, because in one’s youth, one feels things more intensely and the whole world is filtered by accentuated feelings and sensations. People often ask me if the book is about my own experience. My answer is that it is roughly based on my story but with some creative licence. After all, poetry is a form of creative writing, and poets can exercise a certain degree of creative freedom. Poetry should not be conflated with autobiography or memoir. The book is, therefore, an account of how I recreate a younger version of the self, imagine that person’s life and their feelings, and try to figure out how I relate to that person.

Simon, your poems contain code-switching between English and Manx Gaelic, together with numerous cultural references to Manx culture and folklore. The book therefore has a lot of footnotes and a five-page-long list of endnotes. I enjoyed reading them and have learned a lot! Why do you decide to use Manx Gaelic in your writing, and how do you decide if, when and to what extent to translate and explain things?

Simon: In exploring where I was born and where my father’s family dates back centuries, I don’t think it would be authentic to ignore the Manx language and dialect. Language isn’t just words, it’s culture, history, social practice, politics – everything. It is both a product and source of all those things, and its loss is all the greater for it. As with other languages, there are words that can’t be translated directly into English, or even have a different meaning if done so literally, so there is much ‘loaded into’ using Manx Gaelic within my work.

The Manx Gaelic or Manx dialect that I use is most often where the Manx is the only or most commonly used word or expression, rather than the translation, so it wouldn’t make sense to use English. I also use Manx where it better expresses the poetics – emotion, ‘factual’ accuracy of a situation or place, or that the sound is better!

The decisions on how to ‘deal with’ the Manx and Manx dialect are a point of contention with some. The first decision was not to show the Manx in italics, which would ‘other’ the language. At the last minute, I did the same with the Latin and Welsh too. I decided to follow the way Liz Berry did it with the dialect in her book, Black Country, but to stick to only direct translation. The notes were left to explain the context of the words, hopefully not to explain the poem but to make it meaningful to someone who doesn’t know Manx or the Isle of Man. Maybe sometimes I over-explained things, but Jamie loved the notes, so they stayed.

Your own Section 2, ‘Notes on Belonging,’ beautifully explores ambivalence. In ‘At the Opticians’ you say, ‘I've never known / what a perfect world / looks like, and never / will.’ There is a yearning for ‘...where no one feels the need / to ask or answer / where are you from’ (‘But Where Do You Really Come From?’). Despite that, you say in ‘Why I write in English’ that ‘The English Language / ...offers me / a shelter...’ I'd like to know more about this shelter. What is this shelter? What does it shelter you, or maybe also us, from?

Hongwei: ‘Notes on Belonging’ is largely about the narrator’s identity, childhood and sense of belonging. One often yearns to belong to a community, identity, set of beliefs etc. and find a home, a shelter, for oneself, and this is perfectly common. But as a queer person or ethnic minority or a person living with disability, it is often difficult to fit into the mainstream and its norms. This section, and to some extent the whole book, is about the complex negotiations of belonging and unbelonging. The book often rejects a fixed position and celebrates ambivalence, the in-betweenness.

Despite my rejection of a fixed national and cultural identity, I often find strength writing in a second and foreign language. I did not grow up speaking English. I only started to learn (written) English in my teens as part of my school curriculum. English language teaching in Chinese schools at that time was notoriously ineffective: I learned a lot of grammar but still could not speak. But I was determined to study hard and get good at it because it opened a window to a world vastly different from the mundanity of the small town life I was familiar with.

Later, I took a university degree in English and got a scholarship to study in Australia, and that was the proper start of me learning to use the language. At the age of thirty, I decided to give up writing in Chinese (which I was quite good at, by the way) and start writing in English. Writing in English is still difficult for me today and my work often needs a lot of editing. But that’s fine. Language gives me a shelter in a new country and helps me settle down. It also gives me a tool to express myself and articulate my concerns. I reject the shelter of national identity, but I don’t mind using language as a shelter because language can be both personal and political.

In a way, I see my writing a form of ‘minor literature’, a word that Gilles Deleuze uses to describe the work of Franz Kafka, which subverts both the German language and the order of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. I hope my writing, with its unidiomatic terms and expressions, ungrammatical sentences as well as occasional Chinese characters, can contribute to the pluralisation of English language and literature, challenging the hegemony of Anglocentrism.

I find the forms of your poetry interesting and innovative. ‘Oology’, for example, has a few refrains (‘I had a few, quite a few’), whereas ‘Calls from the Edge’ begins and ends with a series of onomatopoeia (‘We-ow-we – We-ow-we – We-ow-we –We-ow-we’). This gives the poems a folklore and even a folksong quality. Visually, the main text of ‘Calls from the Edge’ is divided into three stanzas and three columns, the letters of two surrounding columns printed in grey. Such a wonderful combination of sight and sound! What are your considerations for using these poetic forms?

Simon: I wrote a lot of poems in two or three columns, way before I eventually discovered the two-column version is called a ‘contrapuntal’ form. I don’t think there is a formal name for the three-column one. Once of my earliest, ‘Meayll Circle’ in Throatbone, came from the fact it is a circle of twelve graves, so the form is three columns in four stanzas (actually also on a curve).

In drafting ‘Calls from the Edge’ I soon became aware that a similar opportunity was presenting itself – it is always the case for me that the first draft, or part-way through the first draft, the potential reveals itself, and then I go with it. I can’t conceive of writing a poem in that form from the beginning. I’d probably freeze. The multi-columned poem provides the opportunity to say two or three different things (and/or ways of saying certain things), so I guess it is a concrete example of what we often try to do within a standard form of poem.

‘Calls from the Edge’ began life in a Will Harris workshop, where he challenged us to find an endangered bird and include an onomatopoeic line within the poem. Being obsessed with both puffins and Manx shearwaters it was probably inevitable that one of them would join the Sumatran Ground Cuckoo. ‘Oology’ was inspired by a story told to me by my Auntie and she used the phrase, I had a few, quite a few, which I found so compelling and decided to use it as a refrain, which then directed, or at least influenced, the poem’s journey.

I found your Section 3, ‘Queer Intimacies’, fascinating for a number of reasons. Firstly, was the choice to address all the poems to 'you' – a partner (or partners). I'm curious why you chose this approach to form, as opposed to a narrative ‘lyrical I’ or a third-person, or a mixture. For me as a reader, it felt like I was a voyeur of proceedings and it imbued the poems with regret rather than the joy, pain or love in the events that you were describing. This wasn’t a bad thing, more so an interesting perspective, but I am interested to hear your comments about it. Also, there appears to me no resolution – do you think that will be a subject of your future writing?

Hongwei: The second-person point of view is indeed less common than the first or third person, but I find it useful for my writing. The first-person alone can seem a bit self-centric, and third person alone can feel a bit aloof. The combination between first person and second person can create a dialogical relationship, as if two people are talking or writing to each other. Many of my poems are like short letters addressed to people (including family members and past lovers or even strangers). So the combined use of first person and second person is appropriate.

The collection conjures up a variety of moods: small happiness, wild joy, minor regret, deep sadness… I hope to take readers through the rollercoaster of emotional journey that is commonly experienced in queer lives. Most of the poems in the book are personal memories; some things happened in the past, some intimate encounters either have not materialised or have failed. That’s why readers could sense regret and feel a lack of resolution. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing. In today’s world, there seems too much emphasis on queer joy, pride, as if problems no longer exist or have been solved. There is a value in looking back in melancholy to remember the pains of growing up, treasure every heartbreak, and see what we may have gained and lost.

My pamphlet Dream of the Orchid Pavilion narrates a more upbeat queer story, by the way. I think we need all modes of existence. I cannot predict the content and direction of my future writing, but I find myself often drawn to melancholic stories. I hope my writing will become more upbeat as I age.

More about your use of poetic forms: ‘Cronk Meayll’ and ‘Twelve Graves’, next to each other on a spread page, are concrete poems whose shapes resemble those of a bald hill or twelve graves. The spatial arrangement of the two poems on a spread page also seems consistent – those deliberately left white spaces seem very striking and even haunting. What do you hope to achieve through the shape of the two poems?

Simon: This is my favourite place on the island, which I also find spiritually nurturing. I always go there ASAP every time I visit the Isle of Man. It is a unique place, a late Neolithic or early Bronze Age circle (c. 3,500 BC) consisting of six pairs of cists or graves called Rhullick-y-lagg-shliggagh (graveyard of the valley of broken slates). I believe there is only one surviving stone circle that is also a grave in the whole of Europe. I have written three poems about this place (below is the one in my first pamphlet, Throatbone) and in all cases they are semi-concrete in the sense that they capture the twelve graves and the idea of a circle, rather than looking like the actual place. For me, including this idea in the poem is crucial for me to connect to the emotionality of the place when writing it.

In ‘Oriental Pavilion’ (Section 4), you explore the difficulties in challenging people for perpetuating racial stereotypes, racism even. People of colour and those of ‘other gender or sexual identity’ so often find themselves in this difficult situation when in ‘alien territory’ – ‘belonging, not belonging, self-excluding, integrating’. You have already talked about your ambivalence when you ‘go home’. Does this mean you don’t have a ‘true home’, or that you have two imperfect ones?

Hongwei: This is a great question. I will probably give you different answers at various stages of my life. But I tend to associate ‘home’ not as a geographical concept (i.e. located in China or the UK) but with the people and things I feel comfortable with. In other words, ‘home’ is what we do to make ourselves comfortable and with our loved ones. It matters less where it is. One can feel equally alienated in China and the UK. In ‘The World End’, the addressee (‘you’) feels equally uneasy in a Yorkshire village where he grew up as the narrator (‘I’) does in a Chinese city. It is the shared sense of queer alienation from their heteronormative families and conservative hometowns that unites the two: ‘Was it this / that had brought us together?’

Another example: in ‘Morning Tea’, I describe the quotidian life of a queer couple in England, where having Yorkshire tea in the mornings becomes a home-making practice despite the two people’s cultural difference:

The tea isn’t the 龍井, 大紅袍

or 鐵觀音 I was used to[…]

But it still tastes like tea,

and it makes me feel at home.

I moved a lot inside and outside China. I have always felt like an outsider wherever I live. My family is what others would call a ‘migrant workers’ family’, and I started taking trains and long-distance coaches alone when I was a child. As a result, I never managed to acquire a local/regional Chinese dialect or develop a long-lasting childhood friendship. Later, I moved around a bit to pursue education and employment. I never really felt like being a local in a place, constantly struggling (until today) to speak and write in a language I’d only really learned in my adult life. Others would often see me as a foreigner and an outsider. I simply could not hide my face and my accent. My queer sexuality has probably also contributed to this constant feeling of alienation and homelessness.

The final poem of the book, ‘Snow in March’, is a poetic musing of my migratory journey from Inner Mongolia (where I grew up) to the English Midlands (where I currently live), via Australia and Germany (where I studied and lived), using snow as a narrative thread. Now, as I age and since I have lived in Nottingham for more than a decade, I have given up the illusion of finding a ‘true’ or ‘perfect’ home; I also feel less lonely and more optimistic. I am beginning to develop a sense of home, not necessarily with a place but more with the people and things I know and love:

Here in the Midlands

there’s no extreme

weather, no intense

love or hate. Quietly

we grow old, just like

the silentf

a

l

lof the

snowflakesdancing

in the airand melting

before theyland.

I do not know whether it is the Buddhist idea of Śūnyatā (‘emptiness’ or ‘nothingness’) the Heideggerian notion of Geworfenheit (‘thrownness’, meaning human beings are thrown into the world) that was in my subconscious when writing these final lines. But hopefully this suggests I am feeling more at home with myself: my body, my sexuality, my ethnicity, my relationship with parents. They used to feel like huge psychological burdens or social barriers, but now they are simply facts of life that I have learned to live with.

My final question. You are a very prolific poet; besides The Whole Island, you have published several pamphlets including Throatbone (UnCollected Press, 2020), Queerfella (The Rialto, 2020), Isle of Sin (Polari Press, 2023), and more recently, a finger in derek jarman’s mouth (Polari Press, 2024) – huge congratulations! Could you say a few words about these books? What are your current and future writing projects and plans?

Simon: Thank you. Unusually, I guess, my debut pamphlet Throatbone was published in the USA. I found, and still find, getting my Manx-focused poetry published difficult, but The Raw Art Review (UnCollected Press) loved it, so I asked if I could pitch a chapbook to them. Thanks to the Manx sister of the Arts Council, Culture Vannin, I ‘imported’ three hundred copies and sold them all!

In November that year, I was incredibly lucky to jointly win The Rialto Open Pamphlet Competition – even more surreal in that I won it alongside Selima Hill. Queerfella (inspired by one of the Manx dialect nicknames for the rattus rattus) charts my journey from shame to unashamed and the re-appropriation of queer.

Throatbone included some Manx queer history (we were only partially legalised in 1992) and I wrote more on the subject in praise of Alan Shea – the man responsible for driving that change. I also wanted to highlight the life of Dursley McLinden. I performed at the launch of the first ever queer history exhibition at the Manx Museum in 2022, but Dursley was noticeably absent. Dursley’s life was an inspiration for the character of Ritchie Tozer in the Channel 4 series, It’s A Sin. I wrote a sequence celebrating his life, but all this queer history stuff didn’t fit The Whole Island (as I didn’t want to expand it into a full collection) so I approached Polari Press who do such a wonderful job promoting queer stories and histories.

a finger in derek jarman’s mouth is another example of my desire to remember our queer history (the threads of which were severely damaged by the AIDS global epidemic affecting the British Isles in the ’80s and ’90s especially). I wanted to publish a tribute to Jarman to mark the 30th Anniversary of his death and was delighted that Peter at Polari Press agreed to publish it alongside a special 130-copy limited edition, which sold out before launch! We are completing a trio of pamphlets in February 2025 with the publication of Patient L1 – a verse memoir in the voice of Jonathan Blake who was one of the first people diagnosed with HIV in the UK, and played by Dominic West in the film Pride. Also, thanks to public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, I am working towards a full-length manuscript, Patient L1 – The Life of Jonathan Blake in Ten Acts. Before that, my debut poetry collection will be published by Out-Spoken Press, expected in February 2026. One day there will be a Manx Collection too, including an exploration of the British-imposed internment camps on the IOM during WWI and WWII. Funnily enough, the locking up and deportation of English-born Jews during the first half of the twentieth century is not a favoured subject in England; but we battle on.

My final question, too: please tell me about your future writing projects and plans?

Hongwei: As mentioned earlier, last year I published a poetry pamphlet titled Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (Big White Shed, 2024), in which I further develop the queer theme to narrate a story about a cross-cultural queer relationship and living between China and the UK. I only started writing poetry in English since the start of the pandemic, and I am a still newcomer to English poetry. So I am still exploring various possibilities and trying to find my own poetic voice.

My non-fiction book, Queering the Asian Diaspora, was published at the end of 2024 by Sage. It is a book about contemporary queer East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) cultural production and politics. It documents and analyses some of the queer ESEA art, film, fashion photography and social activism since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. In recent years, we see a burgeoning consciousness of ESEA identity, community and social activism in the UK and globally. This book seeks to draw an outline of this particular historical moment and also shed light on some exemplary case studies. It also adds an often-missing queer voice to the picture, and articulates an intersectional queer ESEA politics.

I am currently working on a short story collection, provisionally titled Welcome to Destination. In the book, I use the fiction form, especially the form of flash fiction, to explore the queer Chinese migration experience. This book will carry on some of the themes and threads from The Passion of the Rabbit God but will also take them in new directions.

Thank you, Simon, for this wonderful conversation. I have learned a lot from you! I wish you the best of luck for your future projects. Looking forward to our future conversations.

Simon: Right back atcha! as the youngsters used to say. It’s been lovely to hear about your life and poetic journeys, long may they continue. Gura mie ayd. Thank you.

Simon Maddrell’s The Whole Island and Hongwei Bao’s The Passion of the Rabbit God are available directly from Valley Press, and everywhere books are sold.